.

Recalculating base year emissions

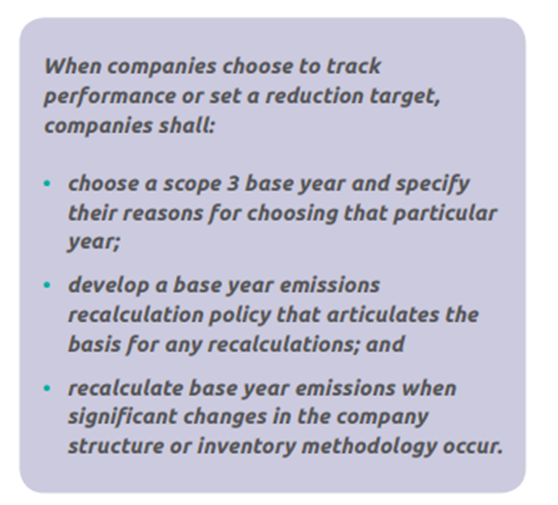

When a company wants to track its emissions over time, they need to calculate a base year to use as a reference point. This base year helps them see if their emissions are increasing or decreasing. However, if the company undergoes significant changes, like mergers, using new methods, or adding new activities to its emission calculations, they should recalculate the base year. This ensures that the emissions data remains consistent and allows meaningful comparisons over time.

These changes that trigger base year recalculation can include:

- Structural Changes: Like mergers, acquisitions, divestments, or changes in company ownership.

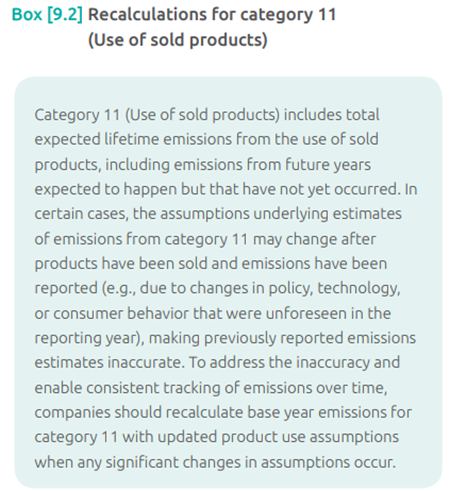

- Methodology Changes: When the way they calculate emissions changes, often due to improved data accuracy or the discovery of errors.

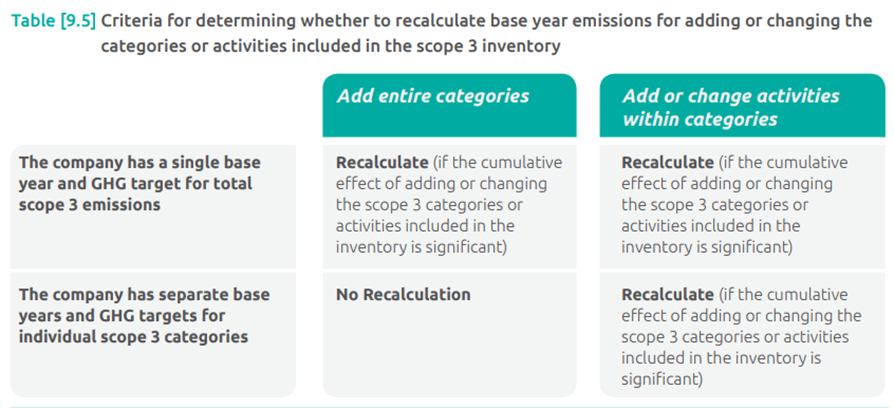

- Changes in Emission Categories: When they add or modify activities in their emission inventory.

To determine whether a change is significant enough to require base year recalculation, companies set a “significance threshold,” a level of change that triggers the recalculation. For example, a significant change could be defined as one that alters the base year emissions by at least ten percent. This threshold helps companies apply their recalculation policy consistently.

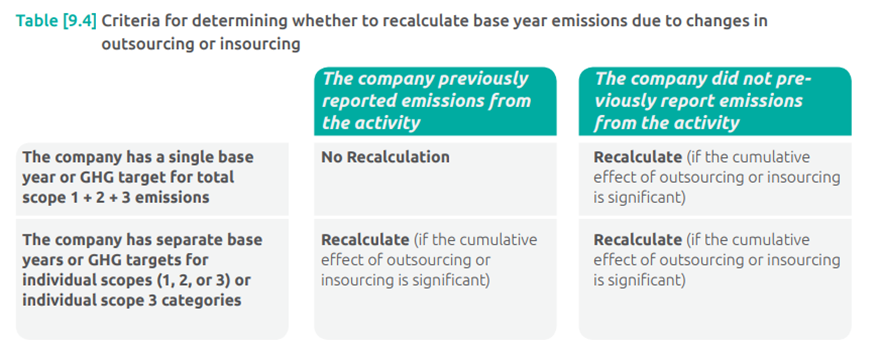

There are specific guidelines for various types of changes, such as structural changes, outsourcing or insourcing of activities, changes in scope 3 activities, and improvements in data accuracy. However, organic growth or decline (changes in production output, product mix, or opening/closing of units) doesn’t require base year recalculation.

Recalculating the base year helps maintain data consistency, allowing companies to accurately track their emissions and make informed decisions about reducing their environmental impact.

Choosing a Base Year and Determining Base Year Emissions: First, a company needs to pick a starting year, called the “base year.” This is the year from which they’ll compare their progress. Then, they figure out how much pollution they produced in that base year.

- Setting Scope 3 Reduction Goals: Next, the company decides how much they want to reduce their pollution, and they set specific goals to achieve that reduction. These goals are like targets they want to reach.

- Recalculating Base Year Emissions (if necessary): Sometimes, a company might need to recalculate the pollution from their base year if they find better data or realize they made mistakes before. This helps make sure the starting point is accurate.

- Accounting for Scope 3 Emissions and Reductions Over Time: The company then keeps a record of all the pollution they produce (called emissions) and any pollution they manage to reduce (called reductions) from their day-to-day operations. This is not just pollution from their own activities (Scope 1 and 2), but also from things like their supply chain, transportation, and product use (Scope 3). They keep doing this year after year.

Accounting for scope 3 emissions and reductions over time

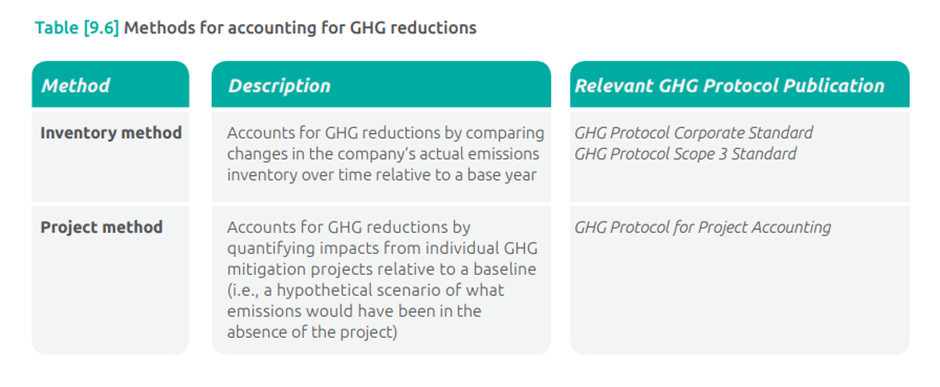

When a company wants to account for the reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions over time, they have two main methods to do it.

Inventory Method

The first method, called the “inventory method,” involves comparing a company’s actual emissions over time to a chosen base year. This way, they can see how their emissions change as they work to reduce their environmental impact. This method is used for all emissions, whether they are direct emissions (scope 1) or indirect emissions (scope 2 or scope 3).

However, accounting for actual reductions in indirect emissions (like scope 2 or scope 3 emissions) is more complicated than direct emissions (scope 1). This is because changes in a company’s scope 2 or scope 3 emissions might not always directly translate to changes in emissions in the atmosphere. For example, if a company reduces business travel, it may lower its scope 3 emissions from travel. Still, the actual impact on greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere depends on various factors, like whether someone else takes the empty seat on the flight or if this reduction affects overall air traffic.

Even though it’s more complex to account for these indirect emissions, companies are encouraged to track and report them over time. As long as these accounting methods recognize activities that, when combined, affect global emissions, it’s valuable for companies to monitor and reduce these emissions.

Project Method

The second method, known as the “project method,” is used for detailed assessments of actual reductions achieved through specific GHG mitigation projects. Companies can use this method in addition to the inventory method to provide more detailed insights into how specific projects impact emissions. However, any reductions from project-based assessments must be reported separately from the company’s general emissions.

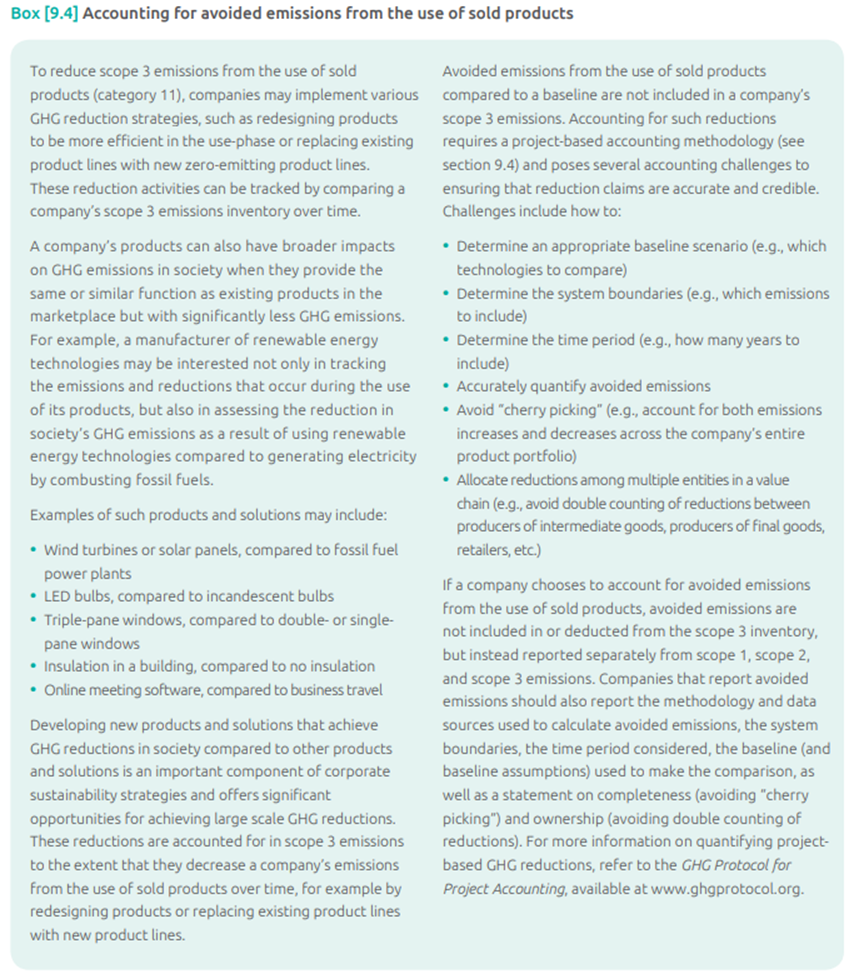

Accounting for avoided emissions

This standard is designed to help companies measure and report reductions in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions for activities not directly under their control. This includes emissions related to the use of their products and services. These reductions are calculated by comparing their emissions from various activities over time compared to a specific starting point called the “base year.”

Now, in some cases, opportunities to reduce GHG emissions go beyond a company’s own activities and also consider the positive environmental impact of their products and solutions. For example, a company might not only look at the emissions generated by the use of their products (like cars) but also consider the emissions that are avoided in society because their products are more environmentally friendly than alternatives. These avoided emissions can also occur when dealing with recycling or in other areas that affect a company’s GHG emissions.

Accounting for these avoided emissions, which are outside a company’s direct control, requires a different method called “project accounting.” Any calculations for these avoided emissions need to be reported separately from a company’s own emissions (whether they’re from their direct activities or the use of their products) instead of being included or subtracted from their total emissions. This ensures a clear and accurate record of the impact of their products and solutions on reducing GHG emissions in society.

Addressing double counting of scope 3 reductions among multiple entities in a value chain

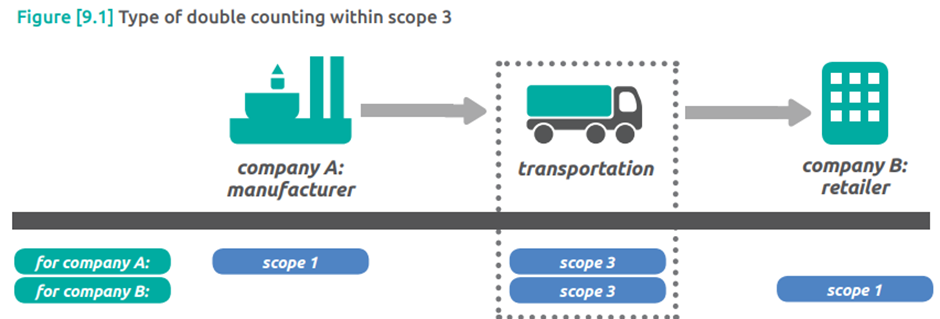

Scope 3 emissions are the indirect emissions produced by other organizations in a company’s value chain. This value chain includes various parties like suppliers, manufacturers, distributors, retailers, and consumers. These entities all play a part in affecting emissions and potential emission reductions, making it challenging to attribute changes in emissions to a single entity.

Now, imagine a situation where two or more companies each try to take credit for reducing the same greenhouse gas emissions from a single source within the same scope (like a transportation company that helps reduce emissions while moving goods for multiple businesses). This is called double counting or double claiming.

To prevent this, there are clear guidelines for companies on how to account for emissions within different scopes (Scope 1, Scope 2, and Scope 3) to make sure that the same emissions aren’t counted multiple times. This standard helps companies avoid double counting when it comes to emissions within Scope 1 and Scope 2.

However, within Scope 3, double counting is a bit different. It can happen because every entity in the value chain has some influence on emissions and potential reductions. For example, both a manufacturer and a retailer might consider the emissions from transporting goods between them as part of their Scope 3 emissions. This is an inherent part of Scope 3 accounting.

Even though some emissions might be accounted for by more than one company within Scope 3, they may be classified differently. This is why it’s important not to add up Scope 3 emissions across different companies in the same region.

Companies might find this kind of double counting acceptable when they’re reporting emissions to stakeholders, working together to reduce value chain emissions, or tracking progress toward Scope 3 reduction targets. However, to keep things clear and avoid confusion, it’s important for companies to acknowledge any potential double counting when making claims about Scope 3 reductions. For example, they might say they’re collaborating with partners to reduce emissions, rather than claiming exclusive credit for Scope 3 reductions.

If these emissions reductions have a financial value or are part of a greenhouse gas reduction program, companies need to make sure they don’t double-count the credits they get for these reductions. They can do this by specifying which company has exclusive ownership of these reductions through contractual agreements. This ensures that the same emission reduction isn’t counted twice.

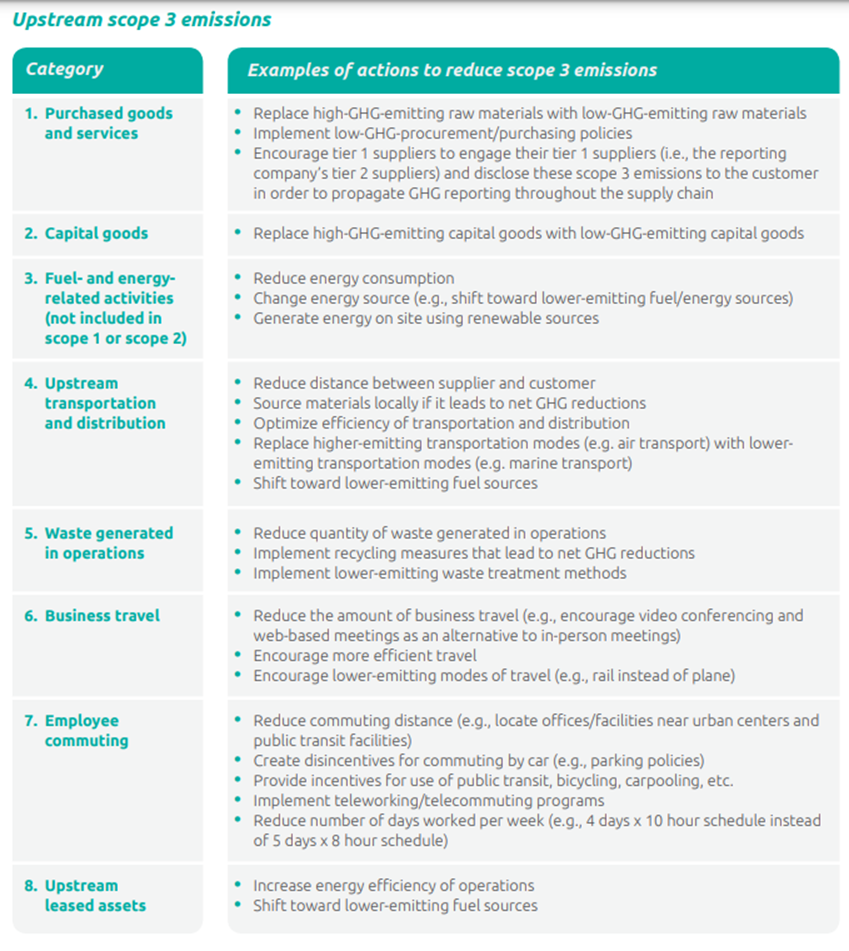

Examples of actions to reduce scope 3 emissions

Companies may implement a variety of actions to reduce scope 3 emissions.